Spiral flute router bits have been around for a long time. But in recent years, the range of sizes and types that are available has increased dramatically. There’s a good reason for this. For many operations — dadoes, grooves, rabbets, edge trimming, or mortising — spiral flute bits offer a sizable advantage over standard straight bits.

THE DIFFERENCE. Originally designed for milling metal, these bits look more like a twist drill bit than a router bit. Rather than being aligned parallel to the shank, the cutting edges (one to four) spiral around it. The end of the bit is not pointed like a drill bit, but is slightly relieved toward the center, like a straight router bit. The result of this design is that spiral flute bits function like a cross between a drill bit and router bit giving you exceptionally smooth, fast cuts.

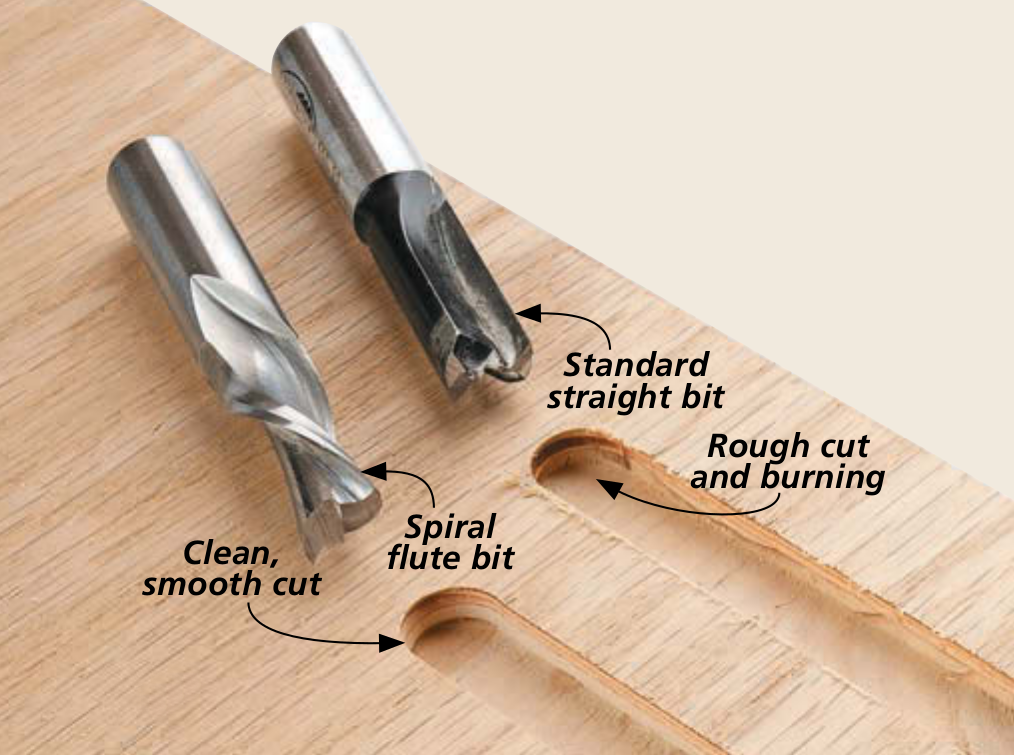

WHY BETTER CUTS? The spiral orientation of the cutting flutes is what provides the “quality of cut” advantage to these bits. And this works on a couple of different levels. The cutting edge of a traditional straight bit attacks the wood with a straight-on chipping or scooping action. This can be the cause of tearout, as well as the scalloped, “chattery” surface that is sometimes seen.

On the other hand, due to the twist, the cut of a spiral flute bit is skewed to the surface. This results in a shearing or scraping cut that leaves a smoother surface.

The second advantage is that, unlike a standard bit, a spiral flute bit is continually channeling the waste away from the point of the cut — either up or down depending on the style of the bit. This rapid clearance keeps the cut from clogging with chips, reducing interference and leading to a smoother surface. A side benefit is that the bit will run cooler and consequently last longer.

UP OR DOWN? The flutes can wind up the shank in a clockwise (called downcut) or counterclockwise (called upcut) direction. The reason for this is that although the cutting action of the two types is essentially the same, each is better adapted to making certain types of cuts. (Both are meant for the clockwise rotation of the router).

WASTE. The direction of the spiral has two effects on the way each type of bit operates. A look at the drawings on the following page will help make this clear.

One consequence that’s already been touched on is chip clearance. An upcut bit works like a twist drill to pull the waste up and out of the cut. A downcut bit does the opposite — pushing the waste downward. When making a deep “trapped” cut, an upcut bit channels the waste up and out. A downcut bit will eject the waste more efficiently during a through cut.

CLEAN EDGES. The second thing to consider is the shearing direction of the bit. When an upcut bit contacts the wood fibers, they’re forced upward as they are severed. The reverse is true of a downcut bit.

At the surfaces of a workpiece, the shearing direction can be important. Due to the upward shear of the cut, an upcut bit will leave a very clean, crisp edges on the opposite or bottom face. But you may get a little fuzz or even chipping on the top surface.

As the photo at the bottom of the opposite page shows, a downcut bit produces the reverse effect. The edges of the shallow dado cut made with a downcut bit are perfectly clean. When routing veneered plywood, this can be a big plus.

You want to choose the bit that produces the cleanest cut on the “show” side. For example, a rabbet or a dado cut with a downcut bit will have a cleaner top shoulder.

BOTH DIRECTIONS. What if the goal is two perfectly clean edges? This is possible. The double-compression bit combines upcut flutes at the tip with downcut flutes along the shaft. It leaves both surfaces crisp and clean, as you can see in the main photo on the opposite page. It’s a great choice for edge trimming plywood and hardwood.

PLUNGE CUTS. Deep plunge cuts with a standard straight bit can be difficult at best. Clogging, wandering, roughness, and burning are often the result.

But a plunge cut with a spiral flute upcut bit is much smoother and easier. The bit essentially drills a hole in the wood, almost pulling itself into the wood while lifting the chips out. For this reason, a spiral upcut bit is my first choice for routing mortises (drawing above).

THE SPECS. Spiral flute bits come in a pretty wide range of diameters — from 1 ⁄ 8 " to 3 ⁄ 4 ". The larger diameter bits may have cutting lengths of up to 1 1 ⁄ 2 ". So you can find a bit to suit almost any application.

Most spiral flute bits made today are solid carbide, although highspeed steel bits can still be found. The carbide bits are two to three times the cost of the steel bits, but they’ll maintain a sharp edge for much longer. In my opinion, this is worth the extra cost.

FLUTE NUMBER. As noted, the number of flutes can vary from one to four. The trade-off is between feed rate and quality of cut. The more flutes, the smoother the cut. But you’ll have to go slower due to less efficient chip clearance. Two flutes seems to be a good compromise.

As the saying goes — “seeing is believing.” And if you’re like me, once you add spiral flute bits to your collection, you’ll wonder how you got along without them. <

Options: Chipbreaker & Flush-Trim

New designs and functions for spiral flute bits are cropping up all the time. The photo at right shows two specialized bits.

CHIPBREAKER.

The example on the above is a finish chipbreaker bit. It’s designed for making fast cuts in hard materials. As you can see, the cutting edges are interrupted by small grooves. The grooves are staggered between the flutes to leave a clean cut along with rapid chip removal.

FLUSH-TRIM.

When flush trimming or pattern routing, you’re often dealing with contours that lead to changes in grain direction and rough, chippy cuts. This is why the shearing cut of the spiral flute flush-trim bit shown above may offer a nice advantage over a standard flush-trim bit.

New designs and functions for spiral flute bits are cropping up all the time. The photo at right shows two specialized bits.

CHIPBREAKER.

The example on the above is a finish chipbreaker bit. It’s designed for making fast cuts in hard materials. As you can see, the cutting edges are interrupted by small grooves. The grooves are staggered between the flutes to leave a clean cut along with rapid chip removal.

FLUSH-TRIM.

When flush trimming or pattern routing, you’re often dealing with contours that lead to changes in grain direction and rough, chippy cuts. This is why the shearing cut of the spiral flute flush-trim bit shown above may offer a nice advantage over a standard flush-trim bit.